Ekolojik (ecological), yeşil (green), doğal (natural), or akıllı (smart): these are the new concepts increasingly emphasized in brochures advertising real estate projects in Istanbul. Stamped with the seal of “sustainability” (sürdürülebilirlik), a terminology that signalled its entry into the vocabulary of Turkey’s urban policies in the early 2000s (Pérouse 2011), do these projects really reflect new forms of urban design and spatial production in the metropolis of Istanbul? In order to answer this question, I provide some context for the incorporation of sustainable urban development (SUD) criteria into the dominant system of metropolitan production. The two sections that follow offer a guide to identifying changes or continuities in the ways of making and designing the sustainable city, through the example of the so-called Bio-Istanbul smart city project.

Conservative Ideology, Real Estate Speculation, Environmental Pressures, and Urban Segregation: Hybrid “Sustainability” in Istanbul

The rapid spread of “eco-projects” in Istanbul coincides with the acceleration, since 2004, in the urban transformation policy initiated by the national collective housing administration (TOKI), an entity accountable directly to the current Prime Minister, which exemplifies the urban ideology of the AKP era. This urban ideology is reflected in an explicit desire to make the city more consonant with the moral and religious values embodied by the AKP. Principles of sustainability are therefore superimposed onto this moralistic aspiration for urban life. The physical manifestation of SUD thus often takes artificial form in the incorporation of a natural, domestic, and safe environment into the built environment.

In the field of urban production in Istanbul, sustainable development, as a new benchmark principle for action, serves the speculative interests of the dominant players, those primarily responsible for the current changes to the city. This metropolitan coalition consists of government institutions that are omnipotent with regard to legislation and land control, such as the Ministry of the Environment and the City, and the big real estate developers with expertise in big international property markets. The recent public revelations about corruption scandals have illustrated the scale of wheeling and dealing in property at the highest echelons of government. The extraordinary social and economic ascent of numerous Turkish property developers is thus explained by the nature and power of the clientelistic relations involving, for example, the son of the current Prime Minister and Erdoğan Bayraktar, recently removed from his position as Minister of the Environment and the City.

In the context of this headlong rush into land speculation, which has made available huge areas of peripheral land for urbanization, environmental threats are becoming ever more perilous. As they stand, so-called sustainable construction projects, designed in the interests of property speculation, do not offer any valid response to the city’s ecological problems. On the contrary, they accentuate deforestation and reduce ground drainage, and are directly implicated in the likelihood of water shortages.[1] This model of urbanization is also partly responsible for the catastrophic floods of 2009 and 2010 (Pérouse 2010). Finally, SUD in Istanbul has become a new tool in the exacerbation of urban segregation. Indeed, the above-mentioned construction programs, with their “sustainable” label, contribute to the process whereby the city is fragmented into high-prestige, gated residential blocks, lush with greenery and potentially energy-efficient. To speak of an urban fabric in describing this type of peripheral urbanization in Istanbul makes almost no sense, given the builders’ total indifference to urban continuities, except with respect to the issue of access. Roads now represent the final threads of physical and social integration in a heterogeneous urban landscape, marked in particular by other, more informal, forms of housing production.

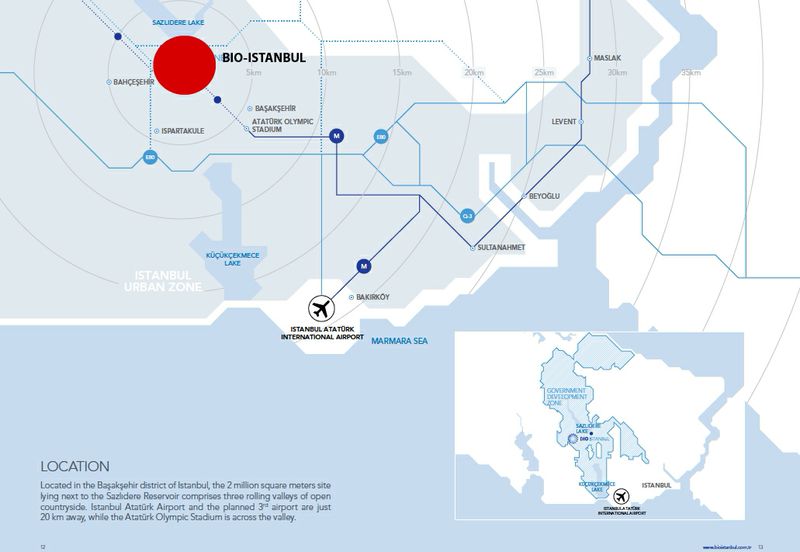

Against this background, let us try to see whether the Bio-Istanbul project, touted as the first large-scale embodiment of sustainable development, is different from these structuring elements of the current system of spatial production. In other words, does this future two hundred hectares’ estate, slated to house ten thousand people, provide a foretaste of the development of a different, non-speculative and non-segregationist model of urbanization, without destructive impact on local ecosystems and metropolitan environmental resources? A simple look at the project’s location would seem to contradict its aspirations to sustainability. The planned location of the Bio-Istanbul project is in the district of Başakşehir, one of the peripheral districts seen as symbolising the AKP’s “hegemonic urban model” (Pérouse 2014), around thirty kilometres west of the historic centre of Istanbul (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Location map of the Bio-Istanbul project (publicity brochure)

Bio-Istanbul: Implementation of New Urban Concepts Geared to the Requirements of a Globalized Innovation Economy

In the early years of the millennium, processes of globalization and liberalization led to a profound restructuring of the health provision sector in Turkey, following the rise to power of the AKP government. These were the circumstances in which, in 2007, the Turkish government made direct contact with the Dutch company Bio-City Development (BCD) with the idea of building a pediatric hospital in Istanbul. This company, officially founded in 2009, was a developer of high-quality infrastructures in the health and biotechnology sector, recognized in particular for its success in the construction of hospitals in London, Boston, and Singapore through the establishment of public-private partnerships. Drawing on this success abroad, and well aware of the opportunities for the health sector in an emerging economy like Turkey, the company convinced the Turkish government to launch a more ambitious project.[2]

Figure 2: The Bio-Istanbul innovation campus:

Turkey’s prestigious international center (publicity brochure)

As a result, with a 320-bed pediatric hospital, a biomedical research center (R&D), an innovation campus offering ten thousand new jobs, and a university, Bio-Istanbul was seen as a future cluster for innovation and economic growth. “Like New Jersey in New York, or Cambridge for London, Bio-Istanbul will be Istanbul’s new medical cluster, located less than sixty minutes from the city center and attracting the greatest names in the health and biotechnology sector,” gushes the publicity brochure (Figure 2). This project served both the interests of the Metropolitan Municipality of Istanbul and the Turkish government, both of which were keen to place Istanbul on a par with other global cities.[3]

The estimated $1.4 billion cost of Bio-Istanbul would be funded by a public-private partnership, along with the development of two hundred hectares of medical infrastructures, combined with 6,500 dwellings, shopping centers, and a leisure center (performance hall, sports center, etc.).[4] Bio-Istanbul Proje Geliştirme ve Yatırım AŞ is a joint venture created in 2010, made up of shareholders of BCD (fifty-five percent), of Emlak Pazarlama Insaat Proje (EPP) (twenty percent), TOKI’s property development subsidiary, and construction firms Artaş (12.5 percent) and Öztaş (12.5 percent). This was Turkey’s first public-private partnership in an urban development project.

Figure 3: Flags of the main developers of Bio-Istanbul

floating over the future development site (Photo Elvan Arik)

This mechanism involves great financial and institutional complexity, which is tricky to decipher. It is indeed difficult to track the capital amounts invested, since they flow internationally between several parallel firms, themselves subdivided into different entities (for example, for land acquisition and development).[5] Initially, Bio-Istanbul will perform the role of land and real estate developer, subsequently taking responsibility for infrastructure management in the new development. With regard to this first role, after investing in the acquisition of the land, in the preparation of the plot and in the pediatric hospital—in order to make the project attractive—the company will issue bonds over a period of seven years, in several phases, to a total value of $220 million, with the aim of attracting new investors. Subsequently, the company will earn money from interest on the bonds, from the sale of the prepared land and the housing units, and from the management of the site’s various activities and functions.

The presentation of the project, to which I was invited,[6] began with the screening of a series of images showing various local real estate programs of high-rise apartment buildings. The speaker cited these images, and the distant presence on the horizon (see Figure 4) of the luxurious apartment tower blocks of Ispartakule, to denigrate what was described as an obsolete urban model. He even went so far as to compare it with the collectivist and hierarchical ideology of Communist cities.

Figure 4: The tower blocks of Ispartakule on the horizon,

and in the foreground the Bio-Istanbul development zone (Photo Elvan Arik)

As an alternative to this failed model, Bio-Istanbul seeks to draw on the past for its sources of inspiration. Its models are thus the gardens of the Alhambra and of the Tuileries Palaces, Ottoman gardens, and the design of Soliman Mosque in Istanbul, together with the cemeteries that dominate the Bosphorus. In this view, the urban history of Ottoman and European cities provide a certain idea of ecology that is now in need of resuscitation. The different visual references that embody this representation of ecology are unified by the quality of the landscape,[7] which is characterized by the predominance of green spaces.

Figure 5: Project model (Photo Elvan Arik)

In any case, the combination of these different influences is not identifiable in the master plan for the new city, drawn by the US architectural firm Swanke Hayden Connell Architects and by the British design office Arup, except to justify the establishment of an “environmental corridor” at the foot of the hills. This landscape corridor extends into the built areas, where building heights are restricted to three stories. Sustainability here is also a synonym for low density, by contrast with the central districts of Istanbul, where the density of buildings and population is presented as the source of all the ills afflicting the metropolis (congestion, pollution, noise, hygiene, etc.).

Bio-Istanbul is thus the amalgam of this purportedly traditional ecology and of modernity—meaning science: “Bio-Istanbul is where science meets nature.” This is a science both produced in the innovation incubators already mentioned, and achievable by application of new technologies in the spheres of safe, clean, and automated transport, integrated waste management, energy from renewables (solar farm and wind farm), and energy efficiency maintained by smart metering systems. This technological concentration is claimed to aim to transform Bio-Istanbul and its inhabitants into an “integrated smart community.”

Economics, Ecology, and Ethics: The Cornerstones of Sustainability in Bio-Istanbul

A generally accepted definition of the principles of sustainable development considers that the three poles of ecology, economy, and society need to be tackled simultaneously rather than in isolation. The designers of Bio-Istanbul have revised this triptych, replacing society with “ethics.” So let us have a look at the ethics of Bio-Istanbul, not so much from a philosophical perspective, but rather in terms of its local potential impacts on the social and environmental dimensions.

At first sight, the Bio-Istanbul product may seem risky in a society dominated by consumerist aspirations, and still poorly versed in the principles of sobriety. This issue of the city’s adaptability to new housing practices is partly bypassed by the targeting of a non-native population, presumed to be already familiarized with, or at least easily receptive and permeable to, the new precepts of eco-living. The explicit purpose of the cluster of innovation around health activities is to attract expatriate Turkish scientists from Europe and Asia—a professional diaspora who migrated because of the lack of resources and technologies formerly available in Turkey. More generally, Bio-Istanbul is designed to meet the expectations of a higher social class with substantial economic and intellectual capital (engineers, journalists, doctors, university professors, bankers, airline pilots, retired professionals). However, this claim about a real estate supply geared towards the ecological sensibilities of the future inhabitants does not stand when we learn that the other target of Bio-Istanbul’s developers is a clientele from the Arabian Peninsula. The Bio-Istanbul project, long kept secret, in part because of the economic recession of 2011, was unveiled for the first time at the City Scape property exhibition in Dubai in 2013, in partnership with GYODER, one of Turkey’s most powerful associations of developers. This “city of the future” created a buzz at the exhibition, and the first sales and investment agreements were immediately signed with wealthy locals. The good relations between Elie Haddad[8] and Abu Dhabi’s royal family were certainly related to the success of this strategy.

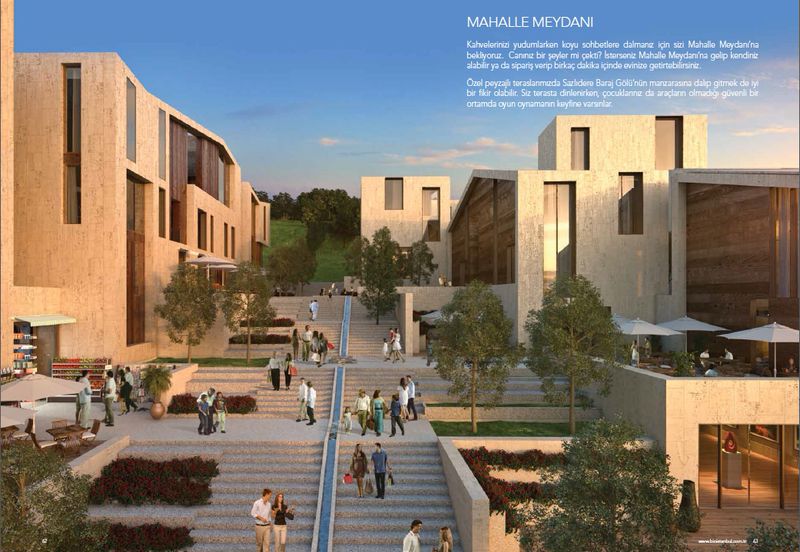

This new city was therefore designed to satisfy an international demand, as evidenced both by its architectural and technological innovations, and the inclusion of specific urban design models. One example is the commercial release process. Within the first batch of six hundred units (150 having apparently been bought already) placed on the market since July 2013, designed by the Turkish-Danish architectural duo Tabanlıoğlu[9] and Saunders, a commercial project, privileging a human scale, will be organized along a pedestrian and shopping street leading into the neighborhood square (mahalle meydani). With this approach, Bio-Istanbul is seeking to offer an alternative model to the immense shopping malls that have proliferated in Istanbul over the last ten years. The appropriation of this “traditional” typology through the reference to the mahalle (neighborhood) seems offbeat, given all the imaginative connotations and representations associated with this figure of the urban landscape. The mahalle is often perceived as an ultimate refuge, offering spaces of social and physical proximity, spaces that are often erased by the process of urban transformation.

Figure 6: The sales offer concentrated around the “neighborhood square” (publicity brochure)

The local landscape amenities of the site where Bio-Istanbul will be developed are also used to consolidate and promote the prestige of the project. Over the two hundred hectares of undeveloped hills, located south of the Sazlidere reservoir, in the district of Başakşehir, there is palpable land pressure on all the ridge lines on the horizon: to the west, the cranes and half-built towers of Ispartakule and Bahçesehir, and to the east the orangey blocks of Kayaşehir, representing now only 15,000 of the 60,000 dwellings in what will become Turkey’s biggest satellite city (250,000 inhabitants).

.jpg)

Figure 7: The site’s landscape quality is a major advertising pitch for the promoters of Bio-Istanbul.

Here, we see the hills surrounding the Sazlidere reservoir (publicity brochure)

In this context of intense real estate development, which threatens the survival of ancient cultural and ecological legacies, could it have been otherwise? From the 1980s until the early 2000s, different local institutions, as well as the heirs of Resneli Niyazi Bey—a Macedonian hero of the war of independence who built a farm near Sazlidere which operated until the mid-twentieth century—had managed to maintain an environmental protection zone, and were working towards the creation of an eco-archaeological park. The rhetoric of ecological sensitivity propagated by Bio-Istanbul’s development company loses credibility here, given the lack of consideration for all this territorial depth characterized, amongst other things, by the richness of its flora. The company claims to have taken all possible measures to protect a rare species of orchid present in the area. However, given the size of the project and, mostly, the location over the hillside of numerous buildings, the excavation and leveling of the site is unlikely to be compatible with this commitment.

In addition, notwithstanding the surprising proximity of the first dwellings to the Sazlidere reservoir, the impact of the project as a whole on the streams and water table was never assessed. Despite the size of the project, no environmental impact study seems to have been carried out. Conversely, what would be the point, given the numerous uncertainties prevailing about the site? If the controversial Kanal Istanbul project were to be implemented, the planned route of the canal would swallow up the Sazlidere reservoir, and would then continue southwards, into Lake Küçükcekemece. As it stands, the consequences of this megaproject on the regional and local scales are hard to fully evaluate. It is certain, however, that it will create numerous—and possibly catastrophic—ecological disruptions, at several levels. Similarly, a question arises with regard to one of the access roads connecting to the third motorway bridge over the Bosphorus which, on one of the models for Bio-Istanbul, crosses the lake at the level of the dam just north of the site (see Figure 5). These large-scale infrastructure projects, and the uncertainty surrounding them, maintain a deliberate dynamic of land speculation on the public plots, most of which belong to TOKI (Morvan and Montabone, 2010). The first dwellings were sold in the summer of 2013, on the basis of €1,600 per square meter, fifteen percent higher than the initial commercial estimates.

Finally, is it possible to interpret what seems to be, at first reading, an integration of sustainable urban development, as a break with the city’s dominant modes of spatial production? As things stand, the answer is clearly negative. The territorial materialization of the principles of sustainability in Bio-Istanbul is the mere reflection of the neoliberal principle—or ethic—of profiteering from land and real estate development. Indeed, SUD is just a new tool of speculation and segregation, enduring space and time, especially if we bet on a burgeoning of such “eco-projects” in the short and medium term. However, we can also posit that the operational challenges of such a project—for instance, in terms of technological governance (notably in the transport and energy spheres)—could trigger a transformation in urban practices and representations of Turkish developers. In this respect, it will be interesting to analyze the forms of professional cooperation that arise between these local actors and global firms (such as General Electric, in the case of Bio-Istanbul), which specialize in the production and provision of “sustainable” urban services.

[John Crisp translated this essay, which was originally published in French on Jadaliyya, thanks to a generous grant from UMR « Environnement Ville Société, Lyon »]

References:

Yoann Morvan et Benoit Montabone, « “Le pont de la rente”. Les enjeux fonciers du troisième pont sur le Bosphore à Istanbul. » Etudes foncières 148, 20‑24 (2010).

Jean-François Pérouse, «Vallées niées, rivières morcelées... La durabilité en danger». Urbanisme 374, 62-65 (2010).

______ «L’impératif du développement durable à Istanbul: une domestication contrariée, partielle et opportuniste». In Expérimenter la «ville durable» au sud de la Méditerrannée. Chercheurs et professionnels en dialogue, (Paris: L’Aube. Monde en cours/ESSEC Villes, 2011), 55-82.

Notes:

[1] Drinking water supply problems are currently re-emerging in Istanbul, with a threat of shortage in summer. While periods of drought, particularly intense this year, are said to be the main cause, loss of ground drainage and poor watercourse management associated with high levels of urbanization need also to be taken into account.

[2] The BCD’s target market is exclusively developing countries, since health spending there is expected to increase very fast to reach the levels of developed countries (i.e. between ten percent and seventeen percent of GDP).

[3] Bio-Istanbul represents the first stage in the building of a global health research network that will be exported to Riyadh, Moscow, Zengzhou, Shanghai, and Ho Chi Minh.

[4] Bio-Istanbul receives the consultancy services of the British firm Savills, the world’s leading real estate consultancy, listed on the London stock exchange.

[5] LandCo, founded in 2010, is affiliated to the company responsible for developing Bio-Istanbul. Its sole task is to buy and sell plots in relation to the issue of bonds. The main stockholder is Bio-Istanbul Proje Geliştirme ve Yatırım AŞ (99.9 percent), while the remaining tenth of a percent is divided between five individual members of CBD’s board of directors.

[6] The bulk of this information was collected during an urban tour organized by the Istanbul Urban Observatory with students of the Masters2 program in Urbanism and Development at Université Rennes II. The objective was to observe the evolution of the ideology, the methods of production, and the urban forms of three generations of new towns located in Başakşehir.

[7] The landscape element of the master plan for Bio-Istanbul was developed by the UK’s Landscape Agency, which seeks to “preserve the character of the site with regard to fauna and flora, architecture and views, so as to reflect local traditions and legacies.”

[8] Elie Haddad, a Lebanese-born engineer, has established close relations with the Abu Dhabi royal family through previous high positions in the Emirates’ investment bank. See the biography of Elie Haddad (p.149 of the hyperlinked report).

[9] This duo of architects is known amongst other things for the design of the Zorlu Center, the Saphhire towers, and the Kanyon shopping center in Istanbul.